Eleftheria Pappa

Senior Fellow, “Migration, Diaspora, Citizenship”

University of Münster

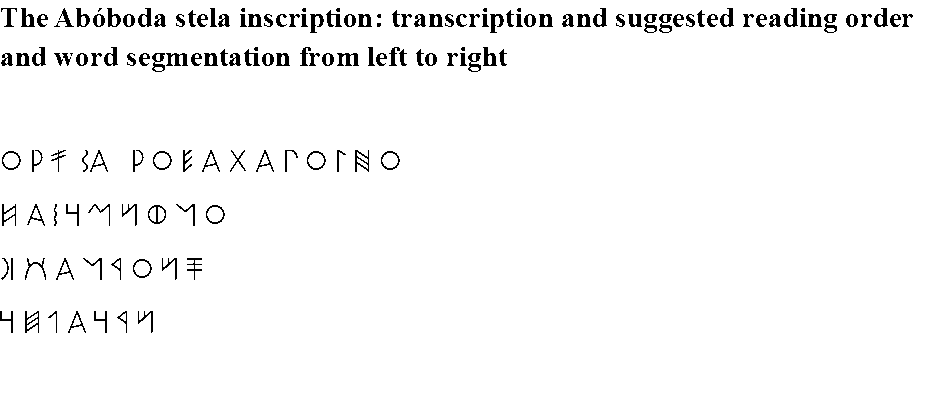

The deciphering of the South-Western script of Atlantic Iberia has seen new recent advances but the consensus, to the extent that it exists, has not facilitated the reading, and even identification, of the recorded language. Suggesting new phonemic values ascribed to the signs, taking into account the inroads that both the Phoenician and Greek scripts made into the Iberian Peninsula (a fact which is archaeologically corroborated), I propose a new reading of the inscriptions that actually both offers satisfying, if partial, readings of the inscriptions, and matches their known context and function. I test the hypothesis presented here using three case-studies: the better-preserved Mealha Nova I and Abóboda inscriptions and the fragmentary Herdade do Pêgo I. This improvement offers new avenues for the reading of the corpus of the South-Western script and the understanding of a Proto-Celtic language spoken in the early 1st millennium BCE and through to the early centuries of Roman annexation.

INTRODUCTION

The enquiry into notions and attestations of citizenship in Iron Age Atlantic Iberia within a migration context, inevitably zeroes in on one of the most valuable cultural assets of migration during this period: literacy. Even if the concept of citizenship -the idea of belonging to a particular, civic community – was not introduced through the migration of peoples from the Near East, i.e. from regions with comparatively more developed political institutions within urbanized societies that affected local forms of community organization or the share of power among populations already settled in the Peninsula, it is literacy that allows us to delve into the matter.

Echoing developments at the other end of the Mediterranean, where the Phrygians, Lydians and Greeks developed alphabetic scripts for their respective languages, the Phoenician consonantal script was adapted in Iberia during the period of Phoenician colonization by several groups, independently of one another. As gauged through the epigraphic record, in this period affected by earlier mass migration, several languages and scripts were circulating at the same time in Iberia. This fissiparous, multi-ethnic population, the result of successive migratory waves into the Peninsula, formed a mosaic of populations with distinct ethnic and linguistic identities, some of which survive to the present as distinct linguistic groups (e.g. Basque).

Brief inscriptions on funerary monuments recorded in the earliest script to be developed in Iberia name the deceased and their links to particular places. This so-called South-Western (SW) or ‘Tartessic’ script is attested in inscriptions on roughly-hewn stone stelae used as grave markers and as graffiti on pottery. About 100 inscriptions on stelae are known, in situ or dispersed within the original sites. Apart from the stone stelae, the SW script is also found as graffiti on pots. They mostly come from southern Portugal (Algarve, Baixo Alentejo), though fewer are known from western Andalusia, and even Extremadura) (Guerra 2010). The script is consistently associated with locations inhabited by indigenous populations in inland area albeit adjacent to major colonial centres or towns immersed in what is presently-termed Orientalizing culture. Doubts about the end point of the use of the SW script derive from the problematic dating of some of the inscribed artefacts and the uncertainty over its relationship to the locally-developed, so-called Paleo-Hispanic script documented in the legends of coins issued by Salacia (Alcácer do Sal) through to the Roman period (Correia 2004), when several cities struck coins displaying toponymic legends in Latin that preserved the Iron Age city names, such as Ossonuba, Baesuris etc (Fig. 1). In some cases, as on the later issues of Salacia, coins bore legends in both Latin and Paleo-Hispanic scripts.

The Latinization of Hispania Ulterior is seen as a gradual process, spearheaded by the social and financial interests of local elites eager to maintain their status (Estarán Tolosa & Herrera Rando 2024). An oft-occurring omission in these discussions is that this process advanced most rapidly in southern Iberia where the urban populations that quickly adopted the Latin alphabet and language had enjoyed literacy for more than half a millennium by the time that the Roman empire extended its frontiers to Iberia, at the very least in the southern portion of the two new provinces, which also facilitated their inclusion into the empire. Although proscriptions against the use of local scripts never appear to have been legislated by the Roman authorities, the adoption of Latin conferred an advantage, independent of Rome’s desiderata: it provided a linga franca in an Iberia that was inhabited by people that spoke multitudes of different languages and used various scripts. Later attestations in the Latin alphabet corroborates this picture, allowing us to chart the linguistic intricacies that the corresponding Paleo-Hispanic epigraphic record adumbrates. Examining the personal onomasticon and ethnic names of several groups, as they survive in historical and epigraphic sources dating to the Roman period, the identification of a Celtic linguistic substratum among the Lusitani and those that the Romans termed ‘Celtiberians’ – an exonym to differentiate this Celtic group that they encountered from the inhabitants of Gaul – is indisputable (García Alonso 2008). Since the Celtic language was not a Roman-era development, the epagogic conclusion must be that the SW script was used to write a form of language that by Roman times was considered Celtic. Far from being a cynosure in studies of literacy in Europe and in the Mediterranean, the SW script possesses the primacy of being the earliest indigenous writing anywhere in western Europe but also in the western Mediterranean, almost of comparable date to the earliest attestations of the Greek language in an alphabetic script. In addition, the subject is of great interest to many other fields that deal with the Bronze and Iron Ages of western Europe, where the investigation into the diffusion of the Celtic language(s) as the result of seaborne migrations or a westward expansion from central-eastern Europe continues to be debated (e.g. Koch et al. 2025). With the mass migration of populations from Greek and Phoenician cities, these languages acquired scripts that were locally adapted from eastern Mediterranean ones. This is not to resurrect ideas prevalent in Vallancey’s (1772) essay on the Irish language being a “collation of the Irish with the Punic Language”, but instead to explain a script used to record a Celtic language within the multi-ethnic historical context.

For any inscription to be read, first the script has to be deciphered, then the language identified and finally, the pinnacle of this process ensues with the aid of historical linguistics. The existing consensus on the SW script is that the first step has been almost accomplished. The vexing problem in this regard is that this deciphering method has not allowed for any reading of the inscriptions, despite the fact that the language is most likely an early form of Celtic. Artefacts inscribed with the SW script continue to be found, yet with little advancement in knowledge on the script per se. It has not helped that these ancient inscriptions are published often without the ancient signs as documentation but with their assumed and contested phonemic values, even as there is no consensus on the deciphering of the script. Moreover, it is almost implicitly assumed that there existed some form of state-like oversight from the beginning, tasked with the systematization of the script and that all variants have to reflect some new sound or orthographic combinations of signs. As early documents of a Celtic language written in an earlier form of script, their reading suffers from an ill-guided consensus on the deciphering of the script, on principles established more than half a century ago, which prevents the actual reading of the script. The fact that these SW inscriptions, pertaining to the locally-developed Paleo-Hispanic scripts have not been read despite several decades of intensive research is, as tentatively propounded here, due to the erroneous reading of the SW script as a semi-syllabic one, rather than alphabetic, owing to the fact that their study has for several decades adhered to the initial hypotheses devised for a different Paleo-Hispanic script recording a different language, and then applied to the SW script, in the assumption that all Paleo-Hispanic scripts – itself, an umbrella term that masks a modern scholarly presumption on shared unity – derived from a single original script, or were related among them, despite being used to write languages of different language families. This monolithic approach has been compounded by the research area unwittingly turning into the exclusive domain of interlocked groups of researchers whose well-meaning, internal ties functioned as a deterrent from moving on from original premises that over decades have not been entirely successful. This list of observations is all the more important when still, after 60 years and all this intensive research, these inscriptions cannot be read after all.

Throwing the current consensus on the phonetic values of the signs into a tailspin is not the ultimate aim, but a way for a better, deeper understanding of the script and as a result, the society that used it. Setting out to challenge the assumptions in the current deciphering principles of the SW script may seem futile had it been for the sake of it. As an exploit, the revision is rendered necessary by increasing archaeological finds that show that in the 8th-7th c. BCE, a residential Greek community in Huelva (e.g. Llompart et al. 2010), an ancient port situated on the western borderlands of the populations that used the SW script, were leaving dedications to gods in their language and alphabetic scripts – just at the time that the SW began to emerge. This fact, when properly understood, injects a whole new dimension to the phenomenon of the emergence of the script. Here I propose new reading for some inscriptions for which high-resolution photographic material permits the transcriptions of signs, proposing a new transcription for some of them. This provides an avenue for discussing new ways of reading an alphabetic script that recorded a Celtic language, which if deciphered correctly, can open a new window onto a period and region where successive migration movements had resulted in a multi-ethnic Iberian Peninsula by the eve of the Roman colonization, where more than a half a dozen languages and scripts were in use. And in the course of this research, inroads can be made onto neighbouring societies that used the same scripts for another form of Celtic being spoken across the other side of the Pyrenees. In addition, it furnishes results relevant to broader themes, such as the modes of spread of Celtic-speaking populations. The aim is to help move the research forward after decades of rehashing old suppositions that has led to a stultified consensus in efforts to read the language, despite many and several significant advances in the documentation and dissemination of it.

To that end, I test an experimental hypothesis built on the internal evidence of the script itself, its media, but also in the knowledge of the archaeological and historical testimonia that has since emerged, proving beyond doubt that the circulation of Greek alphabets exactly in the region and period where the SW script emerges. I explicate the basis of the initial hypothesis, which departs from recent archaeological finds, build the deciphering model on an existing abecedary, and then test the result using three SW inscriptions. I do not pretend to present a fully developed deciphering system, but reclaim the right to study this material unconstrained by principles that have not exactly worked despite decades of research.

The Espanca ‘signary’ (photograph: author), Museu da Lucerna (2012)